Palliative Wound Care

This document is for informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment provided by a qualified health care provider. All information contained in this document is protected by copyright and remains the property of ProCare HospiceCare. All rights reserved.

There are many types of chronic, non-healing wounds. These include pressure ulcers, diabetic ulcers, arterial insufficiency ulcers, venous ulcers, and malignant wounds.

Pressure ulcers are the most common type of wound we encounter as patients decline, become bed bound, and approach end-of-life. Stage 1 and 2 pressure ulcers cause superficial skin changes, and Stage 3 and 4 pressure ulcers affect the deep tissue framework.¹ Pressure ulcers should be staged depending on damage and presence of certain characteristics. It is important to note that if a wound is healing, reverse staging is not done. If a patient has a stage 3 ulcer that is getting better, we would say that the patient has a “healing” stage 3 pressure ulcer.²

A patient’s initial assessment should include a review of their skin and existing wounds, if any, and an assessment of the risk factors that are affecting wound healing. The Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk is one tool used when assessing patients. It is based on sensory perception, moisture, activity, mobility, nutrition, and friction/shear. Keep in mind, most tools used to predict risk do not account for end-of-life decline, so hospice/palliative care patients may be at greater risk than the scales show.³ Other risk factors for chronic non-healing wounds include obesity, tobacco use, vascular issues, diabetes, elderly, radiation therapy, poor self-care, alcohol use, and neurological issues. After the initial assessment, a plan should be developed that aligns with the patient and family’s goals. If there are emotional or spiritual issues that are contributing to poor self-care or alcohol/substance abuse, consider calling on other members of your multi-disciplinary team (i.e., social worker or clergy) for assistance. Therapy goals, which aim to improve quality of life, should be based on patient prognosis, patient factors, heal-ability of existing wound, type of wound, and patient and family wishes. Goals should include preventing new wounds or worsening of existing wounds, prevent/relieve distressing symptoms, reduce discomfort, reduce risk of infection, bleeding, and odor.³

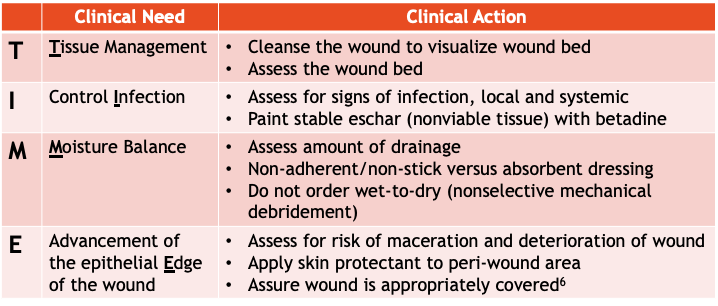

The TIME mnemonic can help us improve wound care.

If a wound has non-viable, deficient tissue, it may need to be debrided. However, stable eschar should be painted with Betadine® and never be debrided.¹² There are many types of debridement techniques including mechanical, autolytic, enzymatic, sharps, surgical, and biologic.¹⁰ Many types of debridement are not appropriate and do not align with goals of care in hospice patients. There are some non-healable wounds that should NOT be debrided. These include arterial wounds in people with Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD) (stable dry gangrene, dry ischemic wound), wounds at risk for bleeding, malignant or inflammatory wounds, lower limb pressure ulcers if arterial insufficiency is present, and wound on patients who are acutely palliative.¹⁰ Most hospice patients have non-healable wounds that should only be debrided if necessary to manage bacterial burden, exudates, and odor.¹⁰

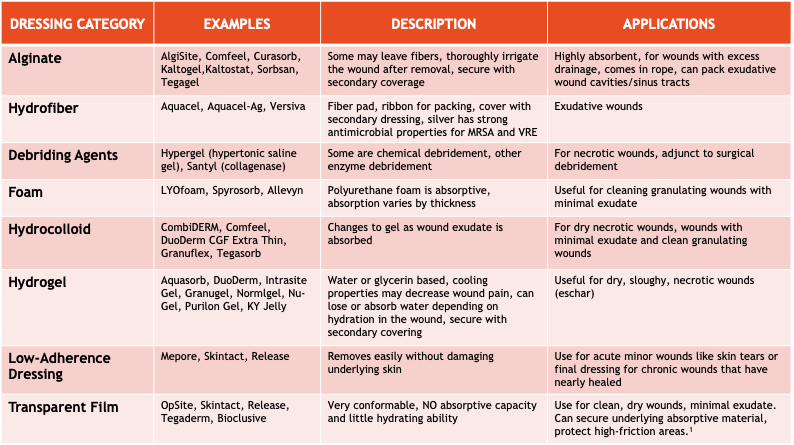

To promote health of the wound, moisture balance must be maintained. The correct dressing will help with this. Dressing choice is based on drainage, non-stick vs absorbent, as well as other factors. Dead space, undermining, and tunneling must be loosely packed or filled with an appropriate dressing. The table below shows the different dressing categories, examples, descriptions, and uses.

Re-evaluate the wound care plan within 2 weeks or if issues arise, or if there are changes in the patient’s condition or patient/family goals. Looking at the edge of the wounds aids in evaluation. Healthy wound edges are attached open and migrating/contracting. Non-healing edges don’t advance or are undermined. Improperly dressed wounds may get tunneling, undermining, and rolled edges. Keep in mind that some patients and family may have difficulty with compliance or procedures and need additional education and support.

Possible wound complications include pain, bleeding, odor, and infection. Moistening dressings before removal, using non-stick dressings, and doing less frequent dressing changes can all help with pain. Using lidocaine 2% gel topically during wound care and/or pretreating with oral morphine or another oral narcotic 30-60 minutes prior to wound care can also help. For pain after dressing changes, consider applying a small amount of viscous lidocaine to the dressing side that contacts the wound.

Malignant wounds are associated with a greater risk of bleeding than other types of wounds. If bleeding is anticipated, it should be discussed with the patient and family, and a plan should be in place. Dark basins, towels and bed linens (not red) can be used to minimize the impact of bleeding. Bleeding can be traumatic for the patient and family. Consider calling on other team members to help provide emotional support if needed. When a wound is at risk for bleeding, use gentle irrigation to cleanse the wound⁴ and stop anticoagulants including aspirin³. Avoid unnecessary dressing changes and debridement. Soak dressings with warm normal saline prior to removal if they adhere to the wound¹³ and use non-stick dressings⁴. If bleeding occurs, calcium alginate dressings can be placed on the wound and direct pressure should be applied for 10-15 minutes. If appropriate, the position can be changed or ice packs can be placed over the wound. Silver nitrate sticks can be used for small localized areas of bleeding. Minimize dressing changes (only changing the dressing if it is saturated with blood). If these methods don’t work, sometimes a sucralfate paste is used to help stop the bleeding.¹³

If wound odor is present, cleanse the wound, treat the cause if possible, and control infection.⁹ Crushed metronidazole (Flagyl®) tablets sprinkled over the wound with dressing changes is an off-label use, but can be effective at controlling odor at a reduced cost. If the wound is in an area where it is hard to sprinkle the crushed metronidazole, it can be mixed with a water-based lubricant and then applied to the wound. For deep tissue infection and odor, oral metronidazole can be used. Honey (Medihoney®) may also be effective for odor, wound pain, and debriding. If these options are ineffective, cadexomer iodine gel or an impregnated dressing (pad) is helpful for odor, beneficial for exudate, and also debrides.⁹ Aromatics can be used in the room to hide the odor. Adsorbents like charcoal (briquettes) or cat litter can be placed discreetly in the room. Baking soda may also be applied between dressing layers. Odor may cause embarrassment, shame, and result in patient isolation.⁹ Multidisciplinary team members can assist in supporting the patient emotionally and spiritually. Taking steps to control odor and talking about it with the patient/family and visitors before they arrive, can be helpful. Chewing spearmint gum, placing peppermint oil under the nose or using Vicks vapor rub can be helpful for the patient and visitors to hide the odor.

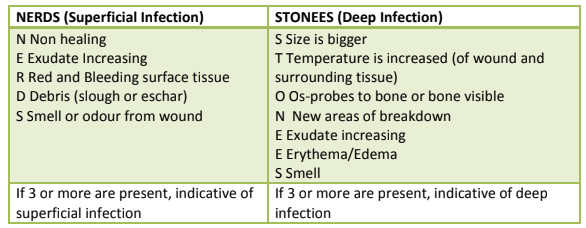

Wounds should be continuously assessed for local and systemic infection.¹² Wound swabs cannot diagnose an infection.² All wounds have contamination and many are colonized with bacteria. That does not mean there’s an active infection.¹² Wound cultures are not appropriate for most hospice patients. They can be very painful and are difficult to perform correctly and without contamination. The pus and necrotic tissue in a wound do not indicate the bacteria contained within the tissue. Also, once a culture is obtained, if not delivered to the lab within an hour, must be refrigerated.⁸

The NERDS and STONEES mnemonic is a useful tool to assess for superficial and deep infection.

Localized infections can be cleansed with topical antiseptics. Consider chlorhexidine, which has low toxicity, povidone-iodine (Betadine®) if broad spectrum is needed, and acetic acid (vinegar diluted 1:5 to 1:10) for suspected pseudomonas. Some topical antiseptics can interfere with wound healing. If the wound is healable, try to limit use and discontinue once infection has been controlled.⁸ After cleansing, topical antimicrobial agents can be used. Crushed metronidazole⁹ and cadexomer iodine that were used for odor, can also be used for localized infection. If these are not effective, silver dressing can be used for a short time, but it is a more expensive option and can cause tissue toxicity and resistance with longer use.⁸

Deep tissue infection may cause further systemic infections. Oral antibiotics can be used to treat systemic infections. The choice to use oral antibiotics depends on if the wound is healable, maintenance or non-healable, and the goals of care. If used, the goal is not to heal the wound, but to control the systemic infection. Expected bacteria in our hospice patients’ wounds are gram positive and negative bacteria including anaerobes. Dual oral therapy is used in order to address all of the different types of bacteria anticipated. The antibiotics used in order of preference are:

- Amoxicillin/Clavulanate (Augmentin®), plus Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) (Bactrim®)

- Clindamycin plus Ciprofloxacin

- Doxycycline plus Metronidazole

- TMP/SMX (Bactrim®) plus Metronidazole

In summary, it is important to do a thorough assessment of all patients for risk of developing chronic wounds and worsening of existing wounds. The main goal for wound care is to improve quality of life. Using the mnemonics TIME and NERDS & STONEES can help improve wound care. Oral antibiotics should only be considered for wounds with deep tissue or systemic infection, and in cases where treatment is preferred by the patient and family. Members of the multidisciplinary team can help support the patient and family and help increase the quality of life for patients with chronic wounds.

Written by: Karen Bruestle-Wallace, PharmD, BCGP, RPh

References:

- Ayello, E. A. (2014, May 12). Pressure ulcer staging. Pressure Ulcer Staging Quality Initiatives. Retrieved January 14, 2022, from https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/IRF-Quality-Reporting/Downloads/IRF-QRP-Training-%E2%80%93-PrU-Staging-May-12-2014-.pdf

- Daley, B. J. (2021, April 3). Wound care. Wound Care. Retrieved January 18, 2022, from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/194018-overview#a5

- Emmons, K. R., Dale, B., & Crouch, C. (2014). Palliative wound care, Part 2: Application of Principles. Home Healthcare Nurse, 32(4), 210–222. https://doi.org/10.1097/nhh.0000000000000051

- Ferris, F., & von Gunten, C. F. (2015, May). #46 Malignant wounds. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. Retrieved January 19, 2022, from https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/malignant-wounds/

- Ferris, F., & von Guten, C. F. (2015, May). Pressure ulcer management: Staging and prevention. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. Retrieved January 14, 2022, from https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/pressure-ulcer-management-staging-and-prevention/

- Kulikov, P. (2018, December 25). Improving Wound Care Using the TIME Framework. The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. Retrieved January 19, 2022, from https://repository.usfca.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1177&context=dnp

- Nurses Association of Ontario, R. (2019). Project ECHO Skin and Wound Infection Enabler.pdf. Infection Control. Retrieved January 22, 2022, from https://drive.google.com/file/d/1HdkywiJhQjZt4ObrPf60_rnfKLaScCqu/view

- Nurses Association of Ontario, R. (Ed.). (2016, May). Assessment and Management of Pressure Injuries for the Interprofessional Team. Clinical Best Practices Guidelines. Retrieved January 20, 2022, from https://wound.echoontario.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/RNAO-2016-Pressure-Injury-BPG.pdf

- Patel, B., & Cox-Hayley, D. (2015, August). #218 Managing Wound Odor. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. Retrieved January 19, 2022, from https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/managing-wound-odor/

- Regional Wound Care Program, S. (Ed.). (2015, April 6). Guideline and Procedures: Wound debridement. SWR Wound Care Program. Retrieved January 19, 2022, from https://swrwoundcareprogram.ca/Uploads/ContentDocuments/WoundDebridement.pdf

- Tippett, A. (2018, April 12). The Use of Lidocaine in Managing Wounds. WoundSource Blog. Retrieved January 21, 2022, from https://www.woundsource.com/blog/use-lidocaine-in-managing-wounds

- Vera, M. (2020, May 6). Wound Bed Preparation and Beyond. WoundSource. Retrieved January 18, 2022, from https://www.woundsource.com/blog/wound-bed-preparation-and-beyond

- Winnipeg Regional, H. A. (Ed.). (2021, April). Malignant fungating wounds - WRHA professionals. Malignant Fungating Wounds, Clinical Practice Guidelines. Retrieved January 18, 2022, from https://professionals.wrha.mb.ca/old/extranet/eipt/files/EIPT-013-007.pdf