Fatigue at End of Life

This document is for informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment provided by a qualified health care provider. All information contained in this document is protected by copyright and remains the property of ProCare HospiceCare. All rights reserved.

Fatigue is defined as a subjective feeling of tiredness, weakness, or lack of energy that can affect one’s physical,

emotional, and cognitive state.

It is one of the most common, distressing symptoms at end of life – ranking up there with pain and anxiety. Yet fatigue is often under-treated and difficult to diagnose, especially when presented with other symptoms that need attention. In fact, patients and clinicians often perceive fatigue as a symptom to be ‘endured’ rather than addressed and managed appropriately. It is also important to document fatigue in the patient’s chart, as it may be a sign of decline.

Fatigue rarely occurs in isolation. In some cases, the cause might not be so clear. You may run labs to identify potential contributing factors (e.g., anemia, electrolyte imbalance), or use scales or assessment tools to index the severity of the fatigue. This helps distinguish it from other common conditions like depression or delirium.

A thorough assessment of fatigue should include the following:

- Complete a thorough history and physical exam (fatigue greater than current activity levels)

- Run labs (optional)

- Use available scales and assessment tools:

- Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS)

- Visual Analog Fatigue Scale (VAFS)

- Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS)

- Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI)

Examples available from: https://www.sralab.org/rehabilitation-measures/; https://www.med.upenn.edu/cbti/assets/user-

content/documents/Fatigue%20Assessment%20Scale%20(FAS).pdf

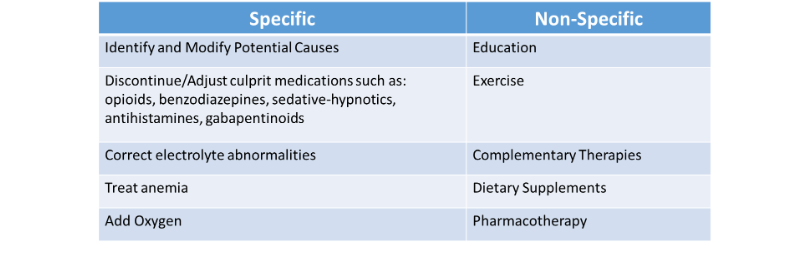

Strategies for Treatment of Fatigue

Non-Pharmacological Interventions

- Patient/Family Education: set reasonable goals based on disease trajectory

- Modify and prioritize high-energy activities

- Exercise (more realistic in palliative care patients)

- Aerobic exercise; goal of 20-30 mins/day, 3 times a week (low-to-moderate intensity)

- Resistance training may be beneficial

- Individualize to patient preferences

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT):

- Most evidence with cancer survivors

- Goal: Interrupt and redirect dysfunctional thoughts and behaviors

Pharmacotherapy for Fatigue

- Reserved for patients who have either:

- Failed non-pharmacological therapies – OR –

- Are not candidates for non-pharm therapies

- Little to no benefit/efficacy found in literature

- Assess the following:

- Interaction check and review adverse reactions (Benefit > Risk)

- Time to benefit

Three Potential Options:

- Psychostimulants

- Methylphenidate (Ritalin) - preferred

- Dose: 2.5 mg (up to 30 mg) BID - QAM and Qnoon

- Efficacy over placebo for improvement in “tiredness” that lasted up to 5 hours in recent study

- Modafanil (Provigil) - non-preferred due to cost

- Cancer-related fatigue, severe (in patients receiving active treatment) (off-label use): Oral - Initial: 100 mg once daily for 3 days, followed by 200 mg once daily during active treatment

- Parkinson disease–related excessive daytime sleepiness (off-label use): Oral - Initial: 100 mg once daily; may increase dose after 1 week to 200 mg/day

2. Corticosteroids

- Treat a variety of symptoms at end of life (portmanteau concept)

- Several Options:

- Prednisone 7.5-10 mg PO QAM; or

- Dexamethasone 1-4 mg PO QAM or BID; or

- Methylprednisolone 32 mg PO daily

- Time to benefit: 1-2 weeks

- Possible adverse effects: risk of infection, hyperglycemia, insomnia, muscle weakness and osteoporosis (long term)

3. Antidepressants: promising benefits in randomized controlled trials

- Bupropion (Wellbutrin) – preferred; 150 mg PO daily

- Time to benefit: 1-4 weeks

- Paroxetine (Paxil) – preferred; 20 mg PO daily

- Time to benefit: 2-4 weeks

In summary, fatigue is a difficult symptom to recognize and successfully treat. It is recommended to utilize an appropriate fatigue assessment tool, along with a detailed history and physical exam. Always individualize a fatigue treatment plan that best suits the patient and their individual preferences, and monitor closely for efficacy as well as any adverse effects.

References:

Esch AE and Newman S. Clinical Care: How to Identify and Treat Fatigue in Our Patients with Serious Illness. Center to Advance Palliative Care. [Online] Available from: https://www.capc.org/blog/how-to-identify-and-treat-fatigue-in-our-patients-with-serious-illness/.

Reisfield GM, Lowry MF and Wilson, GR. Fast Facts and Concepts #173 Cancer-Related Fatigue. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. [Online] Available from: https://www.mypcnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/FF-173-Cancer-Fatigue.-3rd-Ed.pdf.

Ingham G, Urban K. How Confident Are We at Assessing and Managing Fatigue in Palliative Care Patients? A Multicenter Survey Exploring the Current Attitudes of Palliative Care Professionals. Palliat Med Rep. 2020 May 28;1(1):58-65. doi: 10.1089/pmr.2020.0005. PMID: 34223457; PMCID: PMC8241319.

Henson LA, Maddocks M, Evans C, Davidson M, Hicks S, Higginson IJ. Palliative Care and the Management of Common Distressing Symptoms in Advanced Cancer: Pain, Breathlessness, Nausea and Vomiting, and Fatigue. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Mar 20;38(9):905-914. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00470. Epub 2020 Feb 5. PMID: 32023162; PMCID: PMC7082153.

Narayanan V and Koshy C. Fatigue in Cancer: A Review of Literature. Indian J Palliat Care. 2009 Jan-June; 15(1).

Cross LA. Compassion Fatigue in Palliative Care Nursing: A Concept Analysis. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2019 Feb;21(1):21-28. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000477. PMID: 30608916; PMCID: PMC6343956.